Differentiation In The Classroom: The 8 Strategies That Will Support Every Pupil To Reach A Good Standard

The concept of differentiation in the classroom has had a bit of a bad rap recently as school leaders and teachers adopt a mastery approach to teaching. Here Neil Almond explains the 8 differentation strategies that we should be using and how to make sure they’re used effectively in primary school.

To start with, we’re dealing with a situation where there are so many bad differentiation strategies. It’s not hard when trying to implement differentation in the classroom to fall into the trap of differentiating the wrong way, and widening the attainment gap we’ve been trying to close.

Add in that there are many other teaching strategies that provide similar benefits at much lower risk, and some teachers may simply feel that differentiation ‘isn’t worth it’.

But, using a mastery-based approach, it is possible, and ultimately essential, to develop a differentiated classroom in primary school that accommodates the individual needs of all students to create a learning experience that works for all.

Many of the ideas in this post are borrowed from Mark McCourt’s ‘Teaching For Mastery’ (see What is maths mastery? and the Third Space Learning guide to maths mastery resources) and other sources.

The list of ways to differentiate in the classroom below should be a good starting point for you to develop your whole class teaching in a more mastery-aligned way.

To start with, we need to be clear on some important language that is often used among educators, but whose meaning can vary between them. Below I shall outline what I mean by some of these words in the context of providing differentiated instruction.

As a primary maths teacher and leader following a maths mastery focused approach, many of the examples in this post will be maths-based. The differentiation strategies I highlight can be used for any subject, however.

The Ultimate Guide to Maths Assessments

A breakdown of the different types of primary and secondary maths assessments, with strategies and free resources for use in your school.

Download Free Now!Definitions of differentiation and differentiation strategies

What is differentiation?

Differentiation is often defined as tailoring instruction to meet the needs of individual students. However this is too simplistic a definition in my view; we need to look at both what students’ needs might be through different prisms and how we can adjust our teaching and classroom management according to the ways they may present at different levels.

Read more: Adaptive teaching

Differentiation in fluency

When they first learn new mathematical concepts, pupils use much of their working memory to think about what they are being taught.

We know from decades of cognitive science that our working memory – what we can think about in the moment and give attention to – is limited, some say between 4-7 pieces of information.

That is why when we want to remember a telephone number we have to keep on repeating it so that it is not lost from our working memory and forgotten.

Learning, as defined by Kirschner, Sweller and Clark is a ‘change in long-term memory’.

Learners take what they hold in their working-memory and encode it into their long-term memory – a far more complicated process than I have made it sound here.

From our long-term memory we can call upon this information as needed with very little effort – multiplication facts are a good example – and transfer them to our working memory to solve problems.

Fluency then, is the process of retrieving information from our long-term memory with no effort from our working memory, freeing up valuable space in our working memory to give attention to other things.

Read more on cognitive load theory in the classroom and fluency in maths.

We understand that trying to achieve fluency in maths is not always a linear process and can be challenging in whole class teaching. That’s why pupils taking part in Third Space Learning maths tutoring embark on their own personalised learning journey, recapping lessons, and linking to real life examples throughout. Mathematical fluency is developed through continual practice over time, so sessions take place weekly, giving pupils the opportunity to practise applying their knowledge to different types of questions.

Differentiation of ability

When talking about ability, I am referring to an individual pupil’s capability to grasp new ideas and concepts.

An ‘ability gap’ within a class will still be present whether that class is streamed or not. This is far from fixed, and changes in our pedagogy can result in pupils grasping new ideas more quickly and working at a higher level than they may have done previously. With the right learning opportunities more pupils are able to become high achievers.

Read more on teaching for greater depth in maths.

Differentiation of attainment

When talking about attainment, I am referring to the differences between what pupils in the class know.

When we talk about ‘streaming’ classes – this is really what we mean. By setting pupils (or putting them into ability groups within classes), we are trying to limit the range of the attainment gap – the difference between the most that one pupil knows and the least another pupil knows – within classes.

This then gives teachers and support staff a narrower range to focus on while giving high-quality instruction.

It should be noted that in Mark’s book, he recognises that there is no high-quality research into whether classes should be in mixed ability or set.

Read more on mixed ability vs ability grouping in primary.

Differentiation in the classroom as part of your teaching

With those important definitions established, let’s look at our list of ways to differentiate in the classroom that you could use to ensure your whole class is brought up to a good standard.

For the mastery model to work, groups need to be as highly homogenised as possible, meaning the attainment gap in a class needs to be as narrow as possible with understanding that there would be great fluidity between groups.

Generally however this is out the control of the teacher and is a strategic choice to be made by leaders.

Below are eight ways that a teacher could change in their practice to ensure that through their differentiation in teaching everyone is brought up to a good standard.

In essence, these are the differentiation strategies to aim for rather than different coloured worksheets, lesson plans or learning objectives.

List of differentiation strategies for the primary school classroom

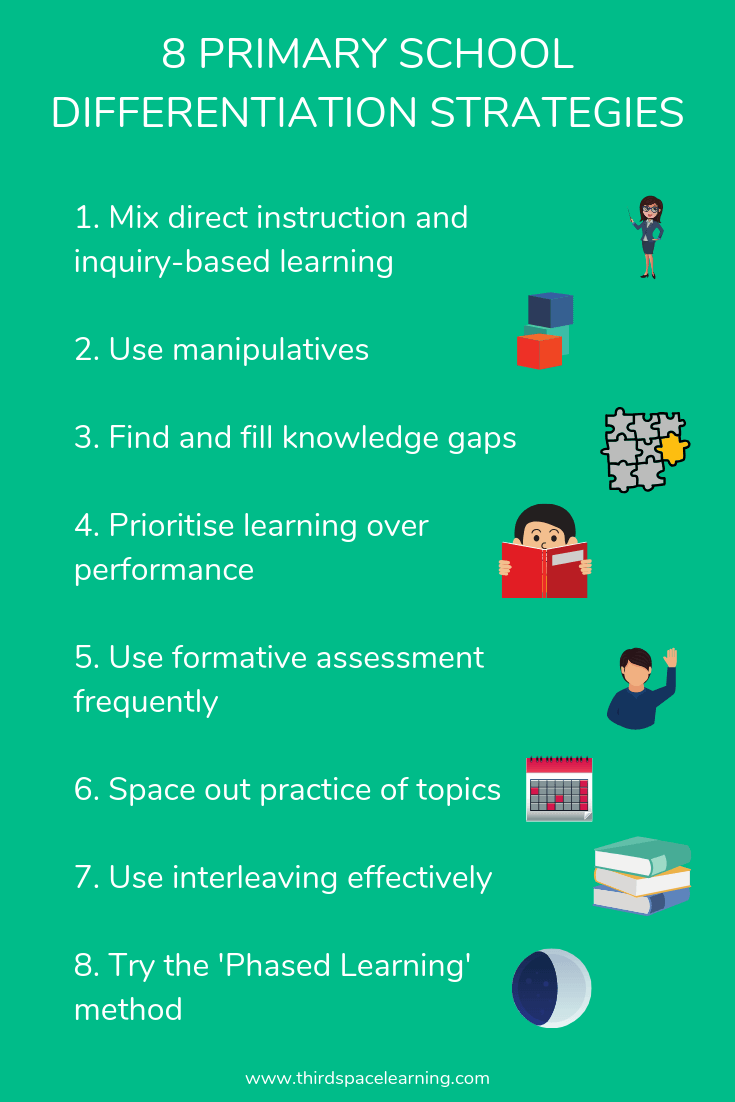

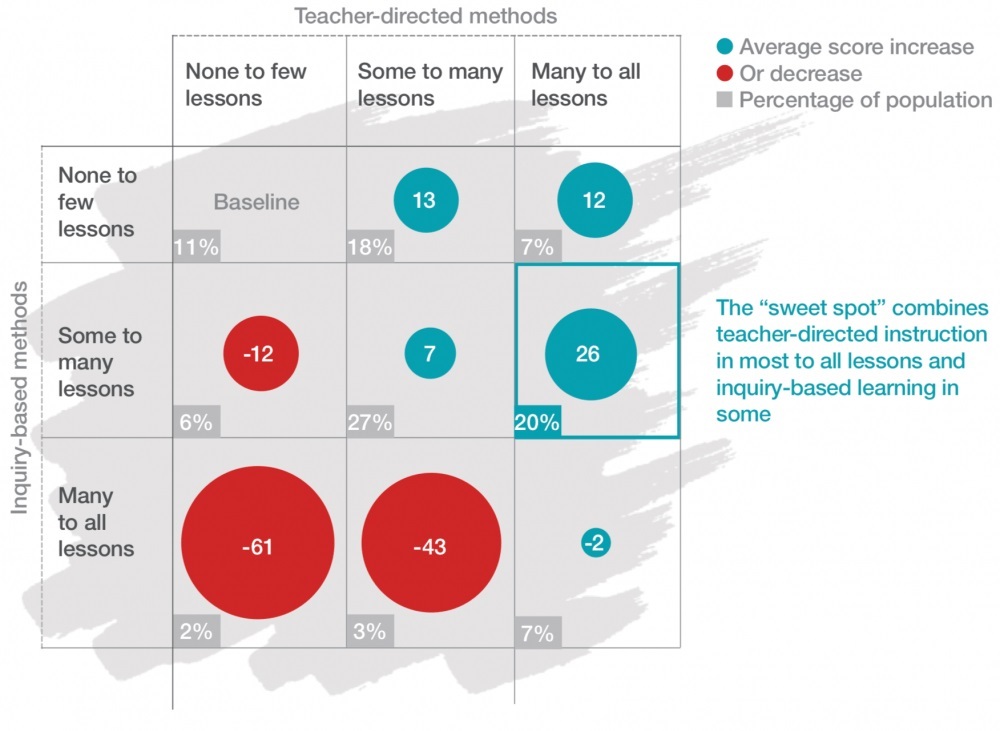

Differentiation Strategy 1: Teach with a mix of direct instruction and inquiry-based learning.

A source of contention that ought to give those teachers with strong positive thoughts about inquiry-based learning a pause for thought.

In order to give pupils the best chance to succeed (and bring all learners up together as one), the majority of our teaching should involve teacher-directed methods.

The table below looks at how different teaching methods impacted on PISA scores.

While every teacher-directed method produced increases overall, inquiry-based methods had a negative impact when used with ‘none to few’ teacher-directed lessons.

Most importantly, it is only when we use a mixture of teacher-directed methods and inquiry-based learning that we optimise the benefits both methods can offer.

Source: OECD PISA 2015, McKinsey analysis

To ensure that the whole class are ‘brought up’ to the same level, it is crucial that we look at the pedagogical choices we make while teaching, and decide whether we’re making the most efficient choices to bring out the best in our pupils.

One of the biggest variables in teaching for mastery is time; we need to use it wisely.

When we can start with direct instruction for pupils about a topic, as opposed to having them discover it for themselves, we should.

Differentiation Strategy 2: Using manipulatives

For those unfamiliar with the term, a manipulative is a physical object used to help teach a concept; they can be anything from fruits to blocks, as long as it enables a child to have a physical example of the concept being taught. They are commonly used as part of the Concrete Pictorial Abstract Approach.

Maths manipulatives allow pupils who are learning new ideas to create mental representations of the subject being taught.

These mental representations help pupils embed conceptual understanding, increasing the chances that they will be able to apply these ideas into other contexts.

Interestingly, a study by Panasuk and Beyranevand (which McCourt cites in his book) claims that those who have deep conceptual understanding perform well on standardised tests, yet the opposite does not hold true. There is limited evidence to suggest that high attainment is a good indicator of deep conceptual understanding.

Manipulation of manipulatives, as well as articulating thoughts and ideas, can help to solidify ideas, concepts or facts and allow pupils to transfer this knowledge to new contexts.

Mark McCourt, in his book ‘Teaching for Mastery’, takes what he calls a ‘mathematical diversion’ and illustrates a range of ways in which he uses Cuisenaire rods to demonstrate a variety of mathematical ideas – including arithmetic with fractions and using negative numbers.

This is a great chapter in his book that ALL primary school teachers should read and stick with.

Differentiation Strategy 3: Find gaps and fill them!

The core purpose of mastery-based teaching is to ensure that no child is left behind.

In an ideal world, the route to mastery would have begun in reception so the year group would be as homogenised as possible.

Obviously, this will not be the case for those looking to begin to implement mastery principles in their current class.

Where there is a large range of different abilities in a class, it is very unlikely that providing challenging and demanding work to the more able students at the top of the range and easier, less demanding work to those at the bottom of the range will decrease the attainment gap in any way.

When differentiation is planned through giving pupils different tasks based on prior attainment, primary teachers are increasing that gap, not decreasing it as the Ofsted framework research overview says.

To close the gap, primary teachers should look to the first element of the mastery cycle and find out what key ideas are missing from a child’s knowledge of a subject – and fill those gaps.

This is when you should be creating or using diagnostic questions which are specifically designed on a range of mathematical content to identify a child’s misconceptions. Craig Barton’s Eedi website has been built around these.

Download 4 Free Year 6 Diagnostic Maths Quizzes (Number and place value, Addition and subtraction, Multiplication and division, Fractions, decimals and percentages). Other free resources are available from the Third Space Maths Hub

Why knowledge gaps appear, and how to close them

As mentioned earlier, fluency is crucial for effective differentiation. For example, when pupils can remember their number facts and are fluent in number bonds to and within 10, the concept of place value, and multiplication facts, they can use a greater portion of their working memory to learn new maths content.

A child who is still reliant on using valuable working memory space to add numbers, perhaps with fingers, is likely to encounter cognitive overload when coupled with new instruction.

This cognitive overload prevents new information from being encoded into the pupil’s long-term memory.

A child who is confident in their number facts is able to recall this from their long-term memory, effectively bypassing the limits of working memory, and use their working memory to focus on the new content.

Gap-filling can even be done “passively”; changing the displays in your classroom topic-by-topic is a great way of enriching pupils’ learning environment with knowledge that can fill gaps without conscious effort from the children.

To help get everyone up to a good standard, ensure that there are plenty of opportunities for fluency and gap-filling. Have pupils quiz each other in pairs or small groups, chant times tables or mnemonics as a whole class – the greater the variety of classroom practices you can differentiate, the better!

Differentiation Strategy 4: Prioritise learning over performance

One of the most interesting findings from cognitive psychology over the last fifty years has been the distinction between performing well on a task and learning from that task.

This finding has made the most profound change on my practise since I began my teaching career.

Before, I would take pupils performing well on a task to be a good indication of pupils learning what I was teaching. It was always a massive frustration when in the next lesson (or in several lessons), I wanted the pupils to use that skill again and many were unable to recall it despite doing well in the original lesson.

This is down to a simple concept that was lost to me during teacher training and the first four and a half years of my career – performing well and learning are two totally different things.

We’re always measuring how well pupils are performing; performance is the interactions with have with them ‘in the moment’, or how many questions they got right on that worksheet.

Yet performing well is a poor proxy for learning. It is easy to fall into the trap of ‘oh, the pupils have got this, let’s move on,’ because pupils are performing well.

So when teachers move onto a topic too quickly based on performance, it is no wonder that the attainment gap increases. We’re essentially skipping part of the learning process, on the strength of incomplete evidence.

To move everyone forward at the same pace, we need to ensure that concepts, facts and truths have been learnt, not performed.

Read more about how to prioritise learning over performance with our posts on deliberate practice and on metacognition in the classroom.

Differentiation Strategy 5: Use formative assessment to guarantee understanding

Formative assessment plays a massive role in bringing everyone up to the same standard. Especially in a class with diverse learning needs, awareness of the breadth of understanding between pupils is key to helping them improve.

Formative assessment crops up three times during the mastery cycle – at the beginning, element three, and element five.

- Diagnostic pre-assessment with pre-teaching

- High-quality, group-based initial instruction

- Progress monitoring through regular formative assessment

- High-quality corrective instruction

- Second, parallel formative assessment

- Enrichment or extension activities

The purpose of formative assessment is to ascertain if the pupil has learned something, and if they are understanding what is being taught.

As educational psychologist David Ausubel put it in 1968, ‘The most important single factor influencing learning is what the learner already knows. Ascertain this and teach them accordingly.’

In Dylan Wiliam’s latest book, Creating the Schools our Children Need, he outlines five main features of short-cycle formative assessment and what teachers can do, minute-by-minute or day-by-day, to ensure high-quality formative assessment takes place.

- Ensuring pupils know what they are meant to be learning

- Finding out what the pupils have learnt

- Providing feedback that improves the pupils learning

- Having pupils help each other learn (group work, peer marking etc.)

- Developing pupils’ ability to monitor and assess their own learning.

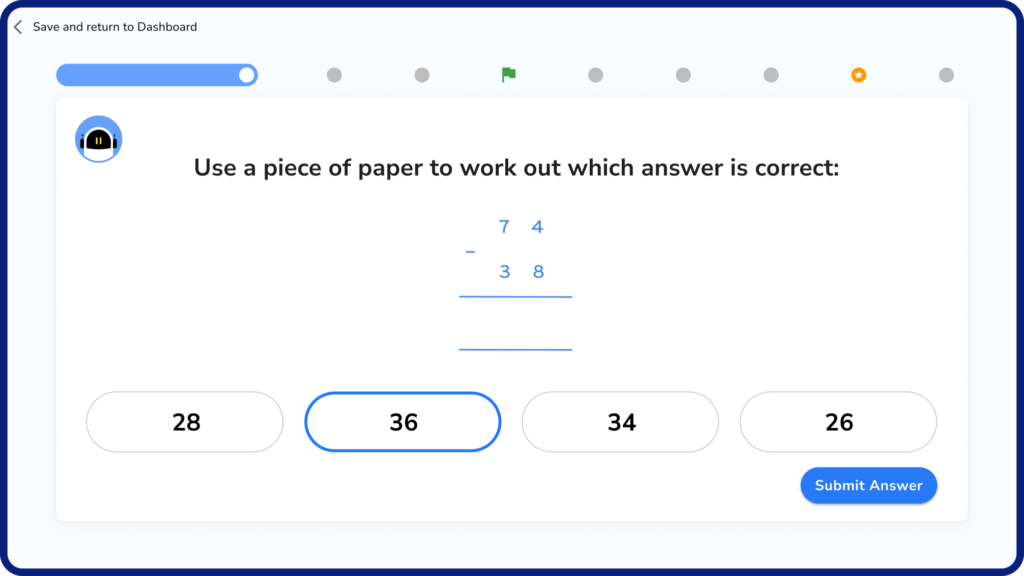

Every Third Space Learner completes an online diagnostic assessment – a kick off quiz – before their first session with their tutor. As well as diagnosing gaps, we also learn a bit more about their attitudes to maths. The results are shared with teachers and tutors to help personalise their learning journey and ensure each pupil receives exactly the right level of support. Teachers can then compare these results with the programme-end quiz to see which gaps have been addressed and which might still need revisiting.

The impact of formative assessment

Recent research conducted by the Education Endowment Fund has found that formative assessment has a positive effect on learning outcomes; those who were involved in the trial gained the equivalent of two months of additional progress.

The other interesting thing they found was that pupils in the lower third for attainment showed greater progress than those in the highest third.

Using assessment for learning: to establish what a pupil knows before teaching them something new; after we have taught them that new topic; and again after we have changed our practice as a result of the first wave of formative assessment, is one way that we can ensure everyone can be brought up to a high standard.

For practical ideas on how to carry out the short-term formative assessment cycle, see Dylan Wiliam’s book, ‘Embedding Formative Assessment’ and Shirley Clarke’s ‘Outstanding Formative Assessment – Culture and Practice.’

Read more on formative vs summative assessment, questioning in the classroom strategies and the importance of a maths diagnostic test for good teaching.

Differentiation Strategy 6: Create lessons with spaced practice

Spaced Practice refers to a specific practice concerned with timing – ‘when’ it’s best to learn.

Is it better to spend seven hours on a Sunday to practise a skill before a test or to space those seven hours out to one hour sessions across seven days?

Many studies have looked into this and the evidence is clear: it would be far better to practise seven one-hour sessions than to practise for seven hours the night before.

Mark McCourt draws on the research of Rohrer and Taylor to illustrate this point. To summarise, three groups were asked to participate in a test and prepare for the test in the following ways:

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week3 | |

| Spacers | Two problems | Two problems | Test |

| Massers | Four problems | Test | Filler Task |

| Light Massers | Two problems | Test | Filler Task |

The gap between practising and taking the test was the same – one week. The final outcome was that those who used the spacing method of practice performed higher than the massed practice categories.

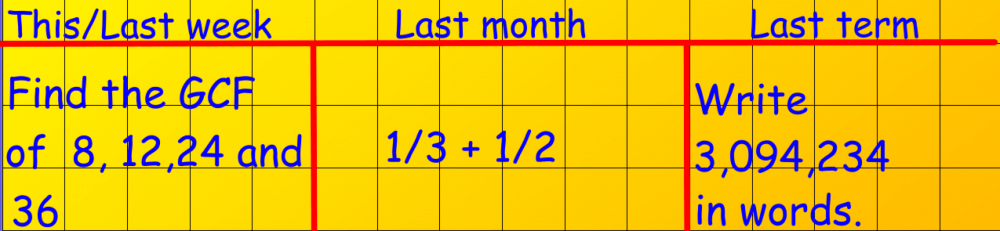

The implication for our teaching (if we want to take advantage of the benefits of spaced practice) is to dedicate some time in every lesson to go over previously learnt material. Since January 2019, I began all my maths lessons the following way:

The this/last week, last month and last term structure proved a useful tool to space out practising of core ideas that the pupils had already been taught.

The pupils had to retrieve this information from their long-term memory; if they failed, this made it clear that the pupils had forgotten the idea, and so I could quickly go over the content again.

I would also consider whether the homework I set should be based on recently taught content, or if it should be used to revisit previously taught content.

Read more on retrieval practice

Differentiation Strategy 7: Interleave effectively!

If spacing is to do with the ‘when’ of practice, interleaving is all about the ‘what’.

In an hour long session, would it be better to spend the whole session practising long division, or would it be better to practise fifteen minutes of long division and fifteen minutes of long multiplication twice over?

Cognitive science is confident that the latter would provide the most benefits to long-term learning.

Note that this should only be utilised once a skill has been taught. It would make very little sense to teach a day of fractions and a day of number and assume pupils can automatically work on them interchangeably.

But once pupils are familiar with concepts, then the practising of those concepts could be interleaved.

The benefits of interleaving have been well documented, and Rohrer and Taylor again have produced maths specific evidence of the benefits of interleaved practice.

They found that those that interleaved their practising two weeks before a test did not perform as well in their practice sessions as those who blocked work into one sitting. But they did score significantly higher than the blockers when it came to test performance, with the blockers achieving 20% accuracy and the interleavers scoring 63%.

Interleaving is particularly useful in teaching the formal long division and long multiplication methods.

What does effective interleaving look like?

To help bring all pupils up to the same level, we should look to interleave new content with previously learnt material once we are sure it has been fully taught and understood.

For example, if fractions have been taught, then that content could be interleaved into perimeter questions.

Another way to interleave would be to put in several questions from a previously taught and unrelated topic into work that is being currently studied.

If nothing else, this would ensure that children gain an awareness of the need to read questions carefully, and avoiding going into auto-pilot when the same types of questions are repeated.

Differentiation Strategy 8: Phased learning in the classroom

This is Mark McCourt’s proposed structure of a learning episode from Teaching For Mastery.

In phased learning, there are 4 parts: Teach, Do, Practice, Behave.

Phase 1: Teach

During the Teach phase, ideas are novel to the learner and the teacher will pass on key knowledge and facts through the use of worked-examples, modelling and metaphor. This ensures that pupils are beginning to make new connections in their schema.

Crucially, no new learning has taken place for the pupil.

Phase 2: Do

The Do phase is to check if pupils have understood all the interaction and modelling from the Teach phase.

The teacher is looking for replication of what has gone on previously. If not, the teacher can change their models and use high-quality corrective instruction to ensure that the pupils can grasp the idea.

The other purpose of the Do phase is to build up a pupils’ confidence in a topic, so that they know they are able to learn the material at hand. Eagle-eyed readers will already be picking up on the crossover potential this has with growth mindset.

Again no learning has happened by the end of this phase, just replication.

Phase 3: Practice

The practice phase is when we seek to move pupils beyond mere performance, and provide the necessary conditions for far transfer – using concepts across different contexts.

This can only be done when true fluency (as defined earlier) has been achieved and the pupils are able to use some of the space in their working memory to attend to the deeper structures of the idea.

Phase 4: Behave

The final phase, which McCourt sees as the most important, is the Behave phase. It is here that learners are given the opportunity to demonstrate deep understanding of the concept.

The content we should expect the pupils to ‘Behave’ should not be the same content that was covered in the previous phases, but rather content already familiar with the pupils.

As Mark McCourt puts it, ‘many teachers find it an uncomfortable – perhaps even illogical – process to plan the ‘Behave’ phase as one that relates to much earlier learning rather than the new idea, but it is crucial to do so if we want to bring about optimal gains in learning, understanding and long term recall.’

Differentiation in the classroom is a tool for long-term results

If we want all different students, with different learning profiles to reach the same level, we need to put learning for the long-term ahead of short-term-gain performances by really looking at our teaching and redesigning it around the ideas and benefits of maths mastery we’ve discussed here.

It’s further worth remembering that it will take time for the full impacts of differentiation in the classroom to be known. There may be some short-term improvements for different groups of students, but the real strength of mastery-based differentiation and other quality first teaching strategies is in the impact they can have across a child’s education.

With the average primary school Year 6 class containing pupils working at very different levels already, one teacher in a class of 30 can struggle to close this attainment gap. However, as the EEF has proven, working in small groups or one to one can have a significant impact on this. This is the reason Third Space continues to provide 1-to-1 maths tuition as the heart of our maths intervention programmes for primary.

DO YOU HAVE STUDENTS WHO NEED MORE SUPPORT IN MATHS?

Every week Third Space Learning’s maths specialist tutors support thousands of students across hundreds of schools with weekly maths intervention programmes designed to plug gaps and boost progress.

Since 2013 these personalised one to one lessons have helped over 169,000 primary and secondary students become more confident, able mathematicians.

Learn about the diagnostic assessment or request a personalised quote for your school to speak to us about your school’s needs and how we can help.